Italian Mountain Running Relays

Autumn: the season of the falling leaves usually draws every mountain runner’s racing streak to an end. After months of grueling up and downs, literally and figuratively, crossing forests, fields and rocks, it becomes time to put away the trail running shoes and enjoy a well-deserved period of rest.

For me, autumn 2017 reserved one big, last event in the international calendar for the very end: the 60th edition of Trofeo Vanoni, featuring the Italian national mountain running relay championship.

At the end of a very successful mountain running season, I was in full marathon preparation: my boyhood dream of running the queen-distance of the Olympic Games was approaching faster and faster. Track workouts, flat long runs and fast reps had replaced my usual mountain running training schedule, but I could not miss Trofeo Vanoni for any reason.

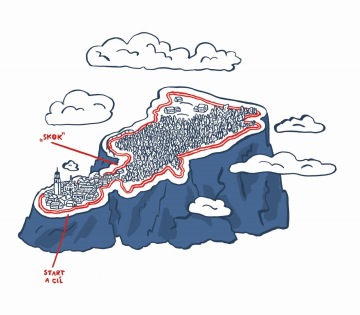

The taste of competition, history and club pride is exalted during a national relay championship. Trofeo Vanoni brings this atmosphere to another level. This year featured its 60th edition, referred to as “the world championship of the falling leaves” referring to the famous cycling race near Lombardy. No other mountain running relay race has seen so many world class mountain runners stepping on its trails as Trofeo Vanoni has. Every year a deep and competitive international field clashes with the very best of Italian mountain runners to crown the strongest and most complete team. Climbing up Valtellina’s southern mountainside, from the historic center of Morbegno to the village of Arzo and back, the classic circuit of 7.25 km and 425 m D+ integrates all kinds of surfaces as well as the iconic rock wall, “The Jump”, which has become the competition’s symbol.

***

On race day, comfortably on time, I spent the morning watching hundreds of young kids animating the streets of the center, sprinting on the cobblestones and proudly wearing their team uniforms. Their dedication and genuine efforts strike a chord within me every time, bringing me back to my first years of running, remembering the short breath and hot tea–cold tears mix after races.

I jogged four or five kilometers, just enough to shake the junk out of my legs and see the lower part of the course. It was oddly comforting to visualize where the main focus would be.

Generally, I like to find a few distractions during the hours leading to a race. Not being new to the environment, I hung out with a couple of friends I hadn’t seen in a while and went off in search of tranquility before starting the warm-up.

Sooner than I had expected, lost in my thoughts, I heard the starting gun. They were off! I yelled at Nadir, my teammate, and the other friends taking off from Via Vanoni as I continued my warm-up, picturing their reappearance around the corner in more or less half an hour.

The sound of applause and “alè-alè-alè!” welcomed Robbie Simpson of team Scotland as he entered the final stretch, setting a 30:03 that would serve as a benchmark for our second leg. My teammate Nadir followed soon after in sixth position, visibly exhausted and with barely the energy to touch my hand and start my run.

The first 300 m felt effortless. I let my strides open and followed a couple of athletes in front of me through the twisting roads of the center before leaving their company on the first ramps. Most of the trail was paved with pebbles, in perfect Valtellinese tradition, with only a few sections with dirt or fallen leaves. At a road intersection I picked up the pace and relaxed my arms before passing another athlete. I was now in second place, aiming straight at the front, which I gained shortly after a steeper section winding through a group of chestnut trees, magnificent in their autumn colors. From that point, the climb became much easier and I tried to focus on fluency while maintaining the highest speed possible, to put as many seconds as I could between me and my chasers. I started struggling a bit, but the meilleur grimpeur intermediate was quickly approaching. I could hear Xavier Chevrier of Valli Bergamasche about 100 m behind me, keeping a constant distance.

Finally, about 20 minutes into the race, I reached the cabins and lodges of Arzo, where the large crowd cheered me on through the last few uphill meters before starting the descent. Narrow and technical trails are the type of terrain where I usually struggle the most: as I soon realized, Vanoni’s descent was undoubtedly one of these. My legs started to tighten and visibility was made difficult by the tears of sweat in my eyes. I kept telling myself, “Just relax, bend ahead and let gravity do the work for you,” like a mantra. Twisting back and forth, the course was rapidly losing elevation taking me towards “The Jump”. A wall of crowds welcomed me with shouts of enthusiasm as I jumped and tried to keep my balance, hearing Xavier coming up just a handful of seconds behind me. The last part of the race was about pushing with all the energy that was left in me. 500 m from the finish I was overtaken. Although I hoped to hang in there, there was no way for me to run faster. I dove on to the finish line and yelled at my teammate Alex, before letting myself fall on the ground in desperate need of oxygen.

Running up a mountain requires a lot of endurance and strength, but considerably slows you down when it comes to shifting the gear and racing on flat land. I like the versatility that the fact of being a mountain runner allows me to develop every season: I’m not too specialized, but at the same time I can switch pretty quickly from one surface to another. With no specific training, I still managed to set the sixth fastest time of the day with 30:11, kindling the battle between my team (composed by Nadir Cavagna, myself and Vanoni’s recordman Alex Baldaccini, whose 28:21 from 2012 makes my head spin) and our historic rivals from Atletica Valle Bergamasche with their three musketeers, Luca Cagnati, Xavier Chevrier and Cesare Maestri. We came short of winning by a mere 21 seconds after 90 minutes of pure, intense racing. I felt like we offered a great show and I felt proud to be part of it. After the race we were sitting all together: the mountain running season was really over and there was no better stage to lower its curtain.

***

Trofeo Vanoni is a striking example of how such a well integrated event in the social fabric and geography of the valley encourages everybody, from the aficionado to the uninitiated, to get out on the roads and cheer for the athletes on the trails and mule tracks. Thousands of spectators, an unchanged setting and the attraction of the relay format: this is how the history of the race blends with the community of Morbegno. The first edition, dating back to 1958, was organized in just a week by the local sport club CSI Morbegno. The course measurement was performed using a 100 m of long rope, and the prize for the winners was a kitchen offered by local sponsors. 21 relays, including two from Switzerland, participated. 200 male relays and over 80 two-element female relays, of which 25 were foreign teams, took part in the 2017 edition.

The winners’ list offers a cross section of the European mountain running scene from the last fifty years. One of the toughest records was set in 1986 by Alfonso Vallicella, Privato Pezzoli and Fausto Bonzi of Alitrans Verona with 1:29:22. It remained unbeaten until 2007, when Forestale’s Marco Rinaldi – Emanuele Manzi – Marco De Gasperi lowered it to 1:28:55, which has stood since then. It’s intriguing to imagine Ian Holmes’s 2007 crazy descent, or Alex Baldaccini’s mind-blowing ascent to Arzo in just 19:30. The women’s race record has a curious story, since it was set in 2015 by Emmie Collinge, a British mountain runner and explorer who established her roots in Valtellina. Before that, it belonged to Anna Pichrtová, who is best known for her 2008 Sierre-Zinal record.

The international stage of Morbegno is cemented by its sister city, Llanberis (Wales) – a name that should sound familiar to mountain running lovers, as it hosts one of the most iconic races in the world, the Snowdon Race. Every year, a selection of rising Italian mountain runners goes to Llanberis and a Welsh team comes to Vanoni as part of the exchange program sponsored by the local administration boards.

***

Relay races are pivotal in the history of Italian mountain running. The epic of mountain running relays has seen every knight of the best teams clashing against each other over the years. The hall of fame of the Italian relay championship has been dominated by various dynasties since the very beginning: first with legendary team Forestale with Lucio Fregona and Davide Milesi, later with Emanuele Manzi and Marco De Gasperi, and Bar Emma Camerata Cornello, Alitrans Verona; Orecchiella Garfagnana, Valli Bergamasche and Valle Brembana in more recent years.

The pathos and intensity of a relay race is higher than a normal race: not only for the numerous audience and hot supporters, but also due to the teammates cheering for you along the course and the camaraderie felt at the finish line.

Since the 1950s, when the first mountain running races appeared across the Italian Alps, relays have enriched the athletic panorama from Piedmont to Friuli. Staffetta Tre Rifugi in Collina di Forni Avoltri (in the Italian region of Friuli Venezia Giulia) is one of the oldest, having organized its 55th edition in August 2017. This three elements relay runs on the slopes of Monte Coglians, the highest mountain in the Alpi Carniche group, and has a very tough and peculiar course connecting three mountain huts. The first leg covers 739 m D+ in 4.5 km up to Rifugio Lambertenghi, the second is a technical traverse of 3.8 km on Sentiero Spinotti, with a bit of up and downs towards Rifigio Marinelli. Runners must wear a helmet because the danger of falling rocks (or falling mountain runners!) is exceptionally high. The third leg dives back into the valley reaching Collina after touching Rifugio Toiazzi. Every year the elite field is seriously impressive: several teams come from the neighboring countries, Slovenia and Austria, but also from as far as the Czech Republic and Great Britain, not to mention the participation of some of the best Italian athletes. In order to perform well, a team must include runners who are specifically prepared for each terrain. Legends of mountain running and cross country skiing have passed from Collina: Manuela and Giorgio Di Centa, Marco De Gasperi, Maurilio De Zolt, and Jonathan Wyatt.

Most often, relays are held on a loop course, which is the same for every runner. Staffetta Sette Torri in Aosta, Trofeo Valli Bergamasche in Leffe and Trofeo Marmitte dei Giganti in Chiavenna are the most important examples. I have had the privilege to run Trofeo Valli Bergamasche, organized by the local team of the legendary Castelletti and Pezzoli families (an institution in the Italian mountain running tradition), three times in the recent years. Coming early in May, it’s a classic season opener and a good chance to test one’s shape before summer’s main events. In addition, the positive rivalry between my team and the hosting society Valli Bergamasche always draws the best out of one another. After a fast start, it’s basically one big 2 km climb followed by a fast descent till the finish line, interrupted only by a couple of painful short climbs that sting every runner’s legs. Pushing at the sound of cowbells, sliding on the mud, sprinting up on the church stairs for the final rush are good memories, along with a memorable post-race party that never fails to surprise. Every year, the attention towards elite runners and organization details makes it a highlighted event in my calendar.

Trofeo Marmitte dei Giganti in Chiavenna lies in the tradition of Val Bregaglia and Valtellina for mountain running. Endless challenges and sport stories have been written on their trails for a race that is already regarded as a classic. Established in 1982, the race criteria originally involved a relay for male athletes and an individual competition for females. The event takes its name from the giant’s kettles found along the course: characteristic circular cavities which result from the erosion of the rock due to currents of water bearing stones, gravel and other detritus. GS Forestale is by far the most represented team in the hall of fame, with legends Rinaldi–Manzi–De Gasperi still at the top of the all-time lists.

The Club Alpino Italiano (CAI) and the National Alpine Trooper Association (ANA) have historically played a role in the promotion and organization of mountain running events, including relay races. Staffetta dei Presidenti, at its 49th edition, and the National ANA Championship, 41 years down the road, have survived up until our days. One of my fondest memories of the sport includes watching Staffetta dei Presidenti on the last wall before the summit, on Monte Palanzone, in a foggy, misty mid-October morning. Runners are greeted by a hot blanket and breathtaking view, if the weather is clear: the summit stands right in the middle of Triangolo Lariano, in the most dominant position between the two arms of Lake Como.

***

The idea of mountain running is simple: connecting people and places, moving by self-powered energy in a mountain environment. Relays have the ability to add something to this intrinsically beautiful concept: this is the value of the team, and this different perspective can make us realize something we were not fully aware of. It is important to preserve the world of relays and the stories that have been written on their trails. They have always put athletes in the heart of their attention, and this is why incredible achievements and feats have been made possible. By balancing between innovation and tradition, they will continue to shape and characterize the essence of our sport, in which WE are the protagonists.

–––

Czech translation of the article was published in B Magazine, Issue 5 (May 2018).

Francesco Puppi and Alex Baldaccini during the 60th edition of Trofeo Vanoni. Illustration © Nikola Hoření

Trofeo Vanoni race course. Illustration © Nikola Hoření